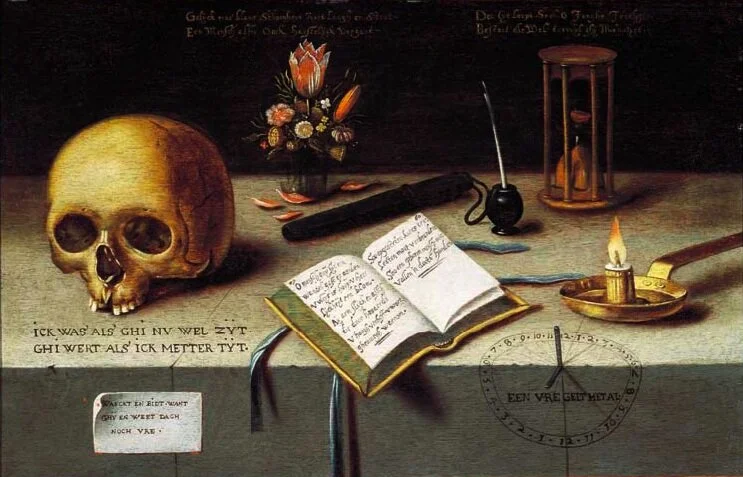

FLEMISH SCHOOL, CIRCA 1620’s

A Vanitas Still Life

oil on panel

17 x 26 inches (43.2 x 66 cm)

Sold to the Flint Institute of Arts, Flint, Michigan

PROVENANCE

Mrs. E. van Stolk, Rotterdam

EXHIBITED

Flint, Michigan, Flint Institute of Arts, To Be, or Not to Be: Four Hundred Years of Vanitas Painting, February 4 – April 2, 2006, number 1

TheJamestown-Yorktown Foundation of the Commonwealth of Virginia, The World of 1607: Concepts of Time, Space and Motion in Science, Philosophy and Art from July 11 2007 – October 10, 2007.

LITERATURE

Raymond J. Kelly, III, To Be, or Not to Be: Four Hundred Years of Vanitas Painting, Flint Institute of Arts, Flint, Michigan, 2006, pp. 20, 34, 50 -51, number 1, illustrated

This work used the emblematic vanitas principle of dependence on text to an extreme degree, almost as if it were an encyclopedia of vanitas paintings. Each vanitas object has its own motto of explication. The skull has the most prominent motto: it says, as if speaking to the viewer, “ I was as you are now; you will be in the future as I am.” The vase of flowers with its central tulip and fallen petals is labeled “As the beauty of the flower does not last long, a person also quickly fades.” Above the hourglass are the words “Time runs fast, all youthful grace vanished before one is aware of it.” The lower half of the marker of time is called “ a metal of oblivion.” On the slip of paper in the lower left, is a command of caution: “Look and pray, or you will face no day of peace.” In the center, the book’s long, two-page poem refers to all these objects:

O human being, you are a wandering guest on earth.

Flesh is the hay of the Lord, like a garden flower

Which by cultivation reaches a higher level of quality (page 59.)

As a lit candle has to burn,

So a man once born must fall into the hands of death (page 60.)

Although these verbal clues are all intellectual commonplaces, the painting offers several unique visual characteristics. Chipped edges and vertical hatchings show that it is a stone ledge on which these objects sit: a harsher, less domestic setting than the more common tablecloth. The twenty-four hour sundial is extremely unusual: the light of day runs from 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., on top of the ledge, while the dark of night, below the ledge, runs from 6:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m. Different times are shown; 2:30 p.m. and 10:00 p.m. indicate that night (unending night?) lasts much longer than the remaining hours of our day. The message of the subscription also lies in shadow. The end nears: most sand has already fallen from the top globe, most of the candle has burned. In contrast to the strong horizontality of the ledge are dramatic vertical lines (the quill, the tulip, the hourglass) and strong diagonals (the quill case, the book, the candlestick’s handle).

This work had formerly been dated to around 1640, but may have been executed somewhat earlier. It has something of the look of the Dutch monochrome vanitas paintings from Leiden in the 1620s and 1630s, although the flowers’ red and the ribbons’ blue hint at Flemish love of color. The starkness of its composition might predate the 1636 arrival in Antwerp of Jan Davidsz. de Heem, whose influence on Flemish painters produced a marked increase in the complexity of their arrangements and the sophistication of surfaces presented. The extensive use of quotations and the distinct positioning of each object make this painting a valuable example of the early, emblematic stage of vanitas.

— Raymond J. Kelly, III

We are grateful to the Flint Institute of Arts for granting permission to reprint Raymond J. Kelly’s entry.